Nailbar

Nailbar - objects and action 2011-2012

As they become anachronistic, many activities - thatching, knitting, wrought iron, stained glass - shift from the domain of skilled workers to the middle class where they hold a new kind of value tied into a specific version of their history. This movement chimes with William Morris’s notion that objects should be made well by happy craftspeople but is challenged by Thorstein Veblen’s idea that the function of labour is to provide a measure of the importance of objects’ owners through reifying the amount of work involved in their production.

New manual skills are less valued, or perhaps not even recognised, by those that mourn the disappearance of old ones. Nail bars are an example of new expertise that can involve a high level of manual skill and complex knowledge of materials and processes.

Contemporary art sometimes has an uncomfortable relationship with manual skill, sometimes questioning its relevance or considering intellectual input more crucial than deftness with materials. Some suspect the artist is potentially a lazy overpaid trickster covertly poking fun at their audience. If a technical skill is evident, the amount of time that has been spent on the work, as well as in gaining the skills in the first place, provides reassurance.

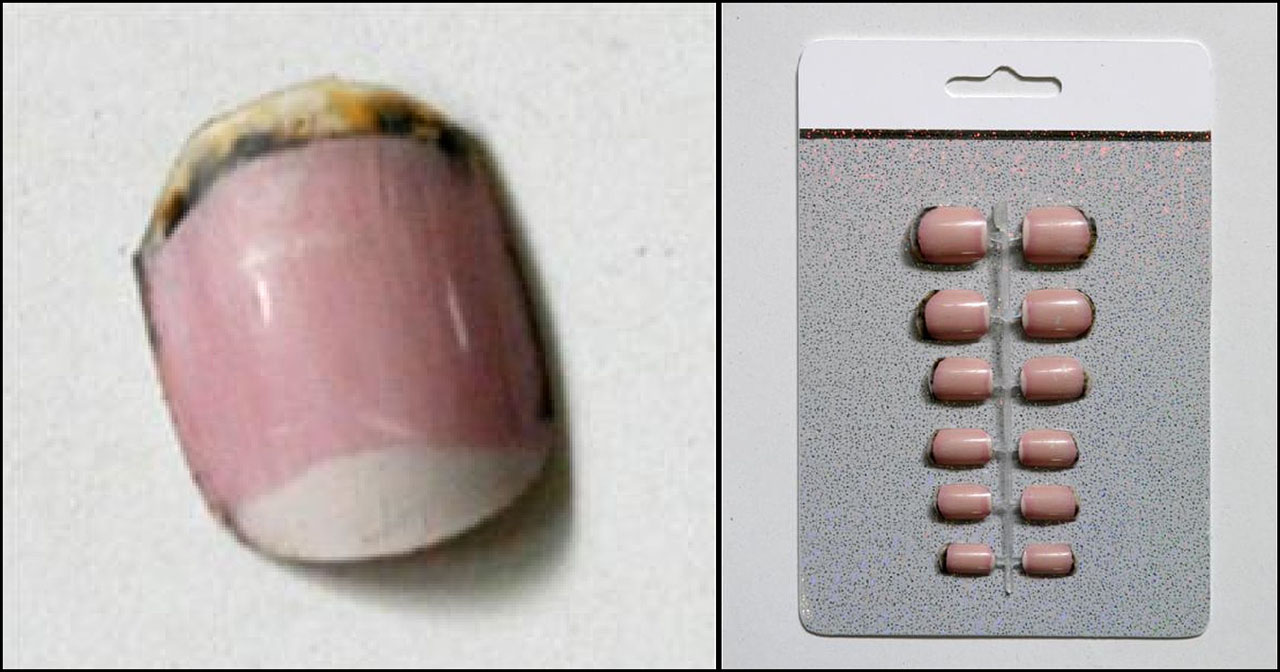

Nailbar questions this standpoint. The dirty false nails have been made skilfully and through careful observation, yet the piece is clearly to do with fakery.

Nail Bar opens up one-to-one discussion about manual skill in relation to work. It does so by looking at class, hierarchy and art. It involves fitting false finger nails that have been painted to look soiled, split, bruised or generally affected by manual work. Each is a tiny painting. Fitting it is an intimate situation involving close physical proximity and touch. It makes time for slow and thoughtful discussion with strangers.